Forestry in Iceland by the numbers

So how is it going?

In over a century of forestry in Iceland, we prevented the destruction of the last remnants of natural forests. We gained experience in forest management and cultivation of a number of tree species. We gained scientifically based knowledge of the best provenances to use, where to plant them and how to get them to live and grow. We have a great deal of knowledge and experience with afforestation of treeless land. We are beginning to develop a real multiple-use forest resource.

Without a doubt, the most important outcome is that there has been a slow realisation among the Icelandic people that we can actually grow forests and reap the resulting benefits. A century ago, most Icelanders had never even seen a tree and knew that trees could not grow in Iceland. Sixty years ago, few Icelanders believed that trees of any size to speak of could grow in Iceland. Planting trees was the harmless hobby of a few eccentrics, but forests for timber production were out of the question. Today, forestry for timber production, land reclamation and amenity is being carried out by thousands of people all over Iceland. Growing forests are both an outcome of and cause for optimism.

As cultivated forests get older and a growing number of them are becoming noticeable in the landscape, it has become obvious to most that a forest resource is developing in Iceland, still small but growing in area. The trees are growing well too. Spacing of young stands has become common and commercial thinning is increasing from year to year. Realisation is increasing of the importance of forests for outdoor recreation, especially around urban areas, resulting in increased emphasis on developing and maintaining the social functions of forests.

Last but not least, afforestation is by far the best means to reclaim and rehabilitate the abundance of eroded and degraded land that characterises much of the Icelandic landscape, changing it to productive and functioning ecosystems, providing habitats for a great variety of life and mitigating climate change in the process.

There are of course still some detractors. They point to potential loss of scenery, nature conservation concerns and a variety of other reasons for being against afforestation. The concerns are usually sincere on the part of the people who hold them and some have merit, at least on a local scale in specific places, but any potential negative impacts of afforestation must be balanced against the positive outcomes. For this reason, good forest planning and management are no less important in Iceland than in countries where forests form a much larger part of the landscape.

The good growth of several tree species has probably been most important in changing people's attitude towards forestry. Several exotic species not much used in afforestation because they don't grow well enough have nevertheless reached between 18 to 22 m in height. Besides the native birch, the major species used in forestry (Siberian larch, Sitka spruce, lodgepole pine and black cottonwood) have all reached at least 22 m in height and show mean annual increments ranging from 5 to 20 m3/ha/yr. Black cottonwood has reached 25 m in height and Sitka spruce is at 27 m as of 2016 and growing fast. Based on growth curves, Siberian larch and lodgepole pine will certainly reach 25 m height on good sites by age 100 years and black cottonwood at least 30 m. Who knows how tall Sitka spruce will get in Iceland? Perhaps 50 meters? In addition to these, roughly 150 species of trees and large shrubs are in regular cultivation in forestry, shelterbelts or for amenity.

The total area of forest and woodland in Iceland has at least doubled, possibly quadrupled, since 1950. Whether this should be considered a large or small increase depends on the comparison. It is large in comparison to the woodland area in 1950, but very small indeed compared to Iceland's land area and to the woodland area at the time of settlement. Native birch woodlands have expanded through natural regeneration within fenced areas but much less in areas not specifically protected from grazing until recently. A recent (2015) remapping of natural woodland extent by the IFS Research Station indicates for the first time that birchwoods are generally expanding and now cover 130 km2 more than in 1990 or a total of roughly 1.5% of Iceland. Cultivated forests cover another 0.4% bringing the total forest and woodland cover to very nearly 2% of Iceland's land area.

For several reasons, planting has not resulted in large land areas being afforested, compared to the area of potential forest land in Iceland. Up to the mid 1980s, land was not available for afforestation because of competition by other land use, especially grazing. Forest establishment is expensive and few individuals have the financial resources to invest in afforesting large tracts of land. Planting by forestry societies was always constrained by lack of money as was planting by the IFS. Afforestation grants to farmers were first offered in the early 1970s but were extremely limited until the 1990s. Due to these constraints, afforestation of relatively large areas has only started within the last 25 years or so.

Iceland has a very small population (330,000) compared to the area of the country (103,000 km2, of which at least 40,000 km2 can potentially be afforested). In other words, there are fewer taxpayers per km2 of land than in neighbouring countries with a similar deforestation/afforestation history such as Denmark, the UK and Ireland. For this reason alone, afforestation through planting, as a proportion of total land area, will likely continue to proceed slowly. Total afforestation planting has been on the order of 1000-1500 ha per year during most of the last 26 years. At that rate, it takes at least 70 years to plant trees on 1% of Iceland's land area.

Since 2005, funding for forestry has been cut in half in real terms, resulting in a proportionately similar reduction in total planting. At the same time, the need for spacing (pre-commercial thinning) is increasing as well as demand for better infrastructure, especially forest roads, foot paths and other things having to do with recreation. Among other effects of downsizing forestry are a greater emphasis by the IFS on increasing other income, such as from timber sales, and proportionately less emphasis on afforestation for land reclamation, erosion control and amenity and less money for research. The dream of afforesting a significant part of Iceland has, for the past 8 years, seemed more distant than it did in the decade before. But, the economy has recovered and forestry is finally seeing an increase in state funding in 2016 and 2017.

In a treeless land, developing a forest resource is obviously beneficial, a no-brainer as some would say. From a historical perspective, it can be seen as rebuilding a resource that was lost and doing it in a way that meets society's current needs. From an ecological perspective, it is a way of reclaiming biological productivity, preventing soil erosion, enhancing ecosystem resilience and much more. From an economic perspective, it can be a way of meeting certain needs in a sustainable manner and decreasing dependence on imports. But developing such a resource requires investment that will not be repaid within the 1-2 years required by impatient (normal) investors. Therefore, it is appropriate that society as a whole make the investment. It is after all not the individual forest owner who will reap most of the benefits, but society as a whole, in the form of jobs, better health, fewer dust storms, better water quality and much more. For today´s society to invest in afforestation that will benefit our grandchildren is the very definition of sustainability.

Society primarily funds what it does through paying taxes, with the government appropriating them. In order to get society to invest in forestry, a widespread understanding of the benefits is required, but mostly it is vital for forestry to have political support, which has recently been lacking. The job ahead for the Icelandic forestry sector is to regain political support for forestry.

Icelandic forestry by the numbers 2016

The following table and figures include some of the latest available statistics in Icelandic forestry. They were provided by Arnór Snorrason and Björn Traustason at the IFS Research Station Mógilsá, Einar Gunnarsson at the Icelandic Forestry Association and the author.

| Native birch forest and woodland cover | 1506 km2 |

| Cultivated forest cover | 400 km2 |

| Total forest and woodland cover | 1906 km2 (1.9% of Iceland) |

| Trees planted 2015 | 3.1 million (~1000 ha) |

| Carbon sequestration in forests planted after 1990 | 210 000 tonnes CO2 per year |

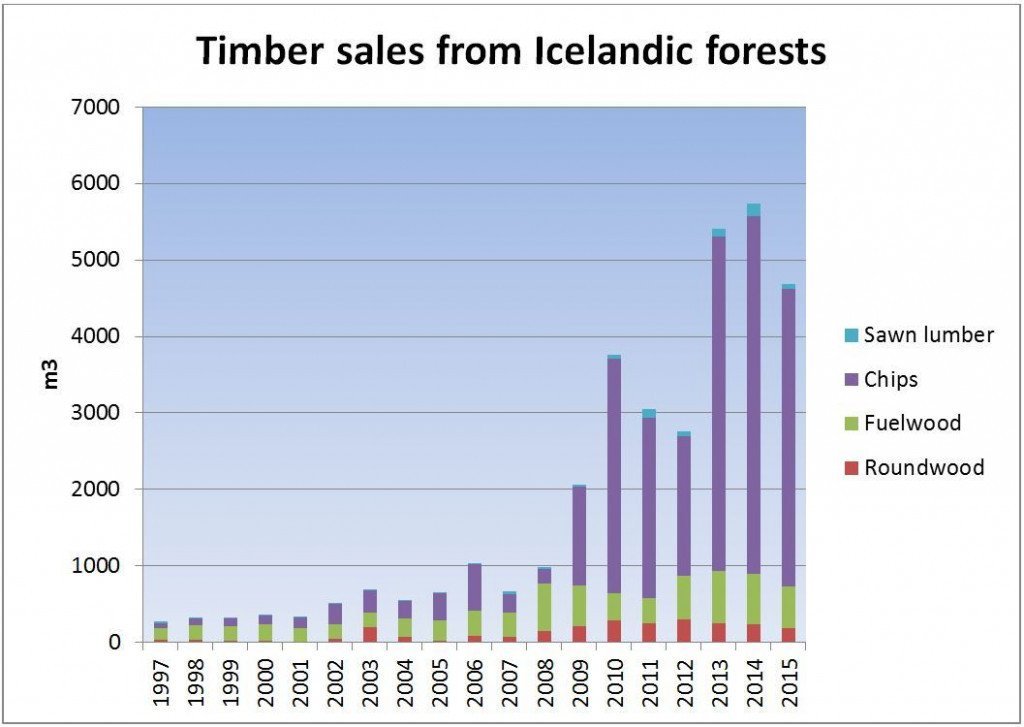

| Timber sales 2015 | 4680 m3 |

| Annual increase in forest extent 1990-2015 | 4.58% |

This figure shows the development of tree planting for afforestation over the past century. After a slow start during the 1940s, planting picked up in the 1950s and reach a maximum around 1960, followed by a 30-year long period of reduced activity. During that time, afforestation took place on state-owned land (the National Forests) and in areas obtained by forestry societies. The increase around 1990 marks the beginning of farm afforestation grants and the Land Reclamation Forests project. The drop after 2009 is partly due to the financial crash of 2008, after which forestry was among the sectors that sustained the greatest cuts in government spending. (Reference: Statistics collected by the Icelandic Forestry Association and published in their journal Icelandic Forestry).

This figure shows the development of tree planting for afforestation over the past century. After a slow start during the 1940s, planting picked up in the 1950s and reach a maximum around 1960, followed by a 30-year long period of reduced activity. During that time, afforestation took place on state-owned land (the National Forests) and in areas obtained by forestry societies. The increase around 1990 marks the beginning of farm afforestation grants and the Land Reclamation Forests project. The drop after 2009 is partly due to the financial crash of 2008, after which forestry was among the sectors that sustained the greatest cuts in government spending. (Reference: Statistics collected by the Icelandic Forestry Association and published in their journal Icelandic Forestry).

This figure shows the development of wood sales from Icelandic Forests and in fact the beginnings of a timber market. “Roundwood” reflects a variety of products but the increase since 2007 is mostly due to sale of spruce poles for fish drying racks, an indication that Icelandic forests are now tall enough in stature to produce such poles. “Fuelwood”, mostly fireplace logs of native birch, was the main wood product from Icelandic forests until about 2008. The increase since 2012 reflects increased use of wood in cooking, i.e. wood fired pizza ovens in restaurants, and is connected to increased tourism. “Chips” are principally used as bedding for livestock, in household heating and since 2009 as a carbon source in silicon smelting. That market finally resulted in much needed thinning in older forests and drove wood sales into the thousands of cubic meters. That is still a very small amount compared to other countries, but a beginning nevertheless. Sales of sawn lumber have increased in recent years, but are still miniscule and will continue to be small for some time to come, or until the forests are on average older and larger in area and final felling commences. (References: Statistics from the Icelandic Forest Service and Icelandic Forestry Association).

This figure shows the development of wood sales from Icelandic Forests and in fact the beginnings of a timber market. “Roundwood” reflects a variety of products but the increase since 2007 is mostly due to sale of spruce poles for fish drying racks, an indication that Icelandic forests are now tall enough in stature to produce such poles. “Fuelwood”, mostly fireplace logs of native birch, was the main wood product from Icelandic forests until about 2008. The increase since 2012 reflects increased use of wood in cooking, i.e. wood fired pizza ovens in restaurants, and is connected to increased tourism. “Chips” are principally used as bedding for livestock, in household heating and since 2009 as a carbon source in silicon smelting. That market finally resulted in much needed thinning in older forests and drove wood sales into the thousands of cubic meters. That is still a very small amount compared to other countries, but a beginning nevertheless. Sales of sawn lumber have increased in recent years, but are still miniscule and will continue to be small for some time to come, or until the forests are on average older and larger in area and final felling commences. (References: Statistics from the Icelandic Forest Service and Icelandic Forestry Association).

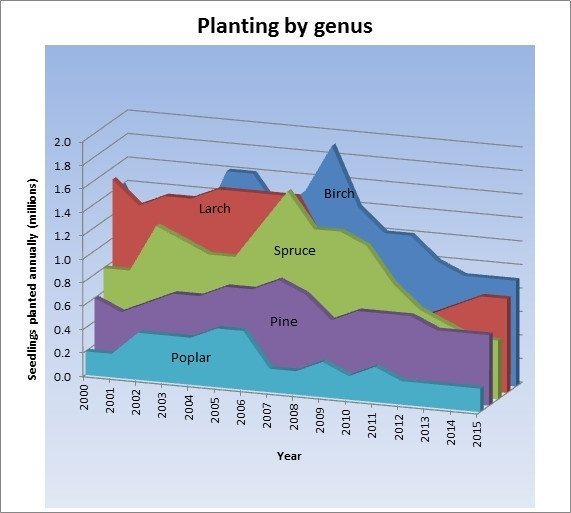

This figure shows total annual planting of the five main tree genera used in Icelandic forestry. The decrease in planting since 2009 affected all species but not equally. Birch planting declined but roughly maintained its proportion of total planting. Larch dipped to low levels due to production problems but is back at a similar proportion as before. Spruce planting sustained the greatest reduction because spruce seedlings are more expensive to produce than birch, pine or larch and in times of cut-backs the tendency is to reduce the costliest production. Pine planting remained more stable and has been gradually increasing as a proportion of total planting since 2001. This is a long term trend resulting from increasing acceptance of lodgepole pine as a timber species in Icelandic forestry. Poplar planting is also more stable but still at a low level for a variety of reasons including concerns about poplar rust, low availability of suitable land and nursery production problems. This figure shows instability in total seedling production and species selection, both of which are reflections of the smallness of Icelandic forestry (small year-to-year changes readily show up) and the fact that forestry is still in development. (References: Statistics from the Icelandic Forestry Association).

This figure shows total annual planting of the five main tree genera used in Icelandic forestry. The decrease in planting since 2009 affected all species but not equally. Birch planting declined but roughly maintained its proportion of total planting. Larch dipped to low levels due to production problems but is back at a similar proportion as before. Spruce planting sustained the greatest reduction because spruce seedlings are more expensive to produce than birch, pine or larch and in times of cut-backs the tendency is to reduce the costliest production. Pine planting remained more stable and has been gradually increasing as a proportion of total planting since 2001. This is a long term trend resulting from increasing acceptance of lodgepole pine as a timber species in Icelandic forestry. Poplar planting is also more stable but still at a low level for a variety of reasons including concerns about poplar rust, low availability of suitable land and nursery production problems. This figure shows instability in total seedling production and species selection, both of which are reflections of the smallness of Icelandic forestry (small year-to-year changes readily show up) and the fact that forestry is still in development. (References: Statistics from the Icelandic Forestry Association).

- History of forests in Iceland

- Forestry in Iceland

- The Icelandic Forest Sector

- Forest Strategy and Forestry Programme

- Forestry in Iceland by the numbers

- Forestry and Climate Change